A short history of Parliament

Compared to some other parliaments around the world, Australia's Parliament is quite young but it is based on practices and ideals from much older parliaments. This in-depth paper explores the development of the Westminster system in Britain and parliamentary democracy in Australia.

The word 'parliament' comes from the French word parler, which means 'to talk'. A parliament is a group of elected representatives with the power to make laws. The fundamental concepts of meeting, representation and legislation – law-making – go back thousands of years. These can be seen in parliaments across the world as well as in other systems of governance such as traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies.

The origins of the concepts of parliament

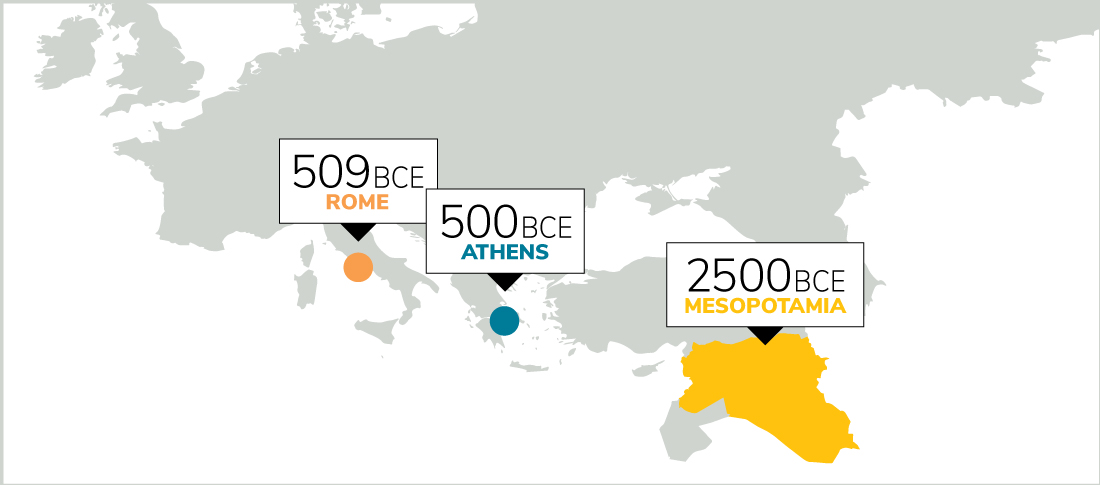

Many ancient cultures featured a gathering of leaders to discuss and decide matters of importance. There is evidence citizens' assemblies were held in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Syria and Iraq) as far back as 2500 BCE. Some of the first assemblies which had elements similar to those of modern parliaments were held in ancient Greece and Rome.

Around 500 BCE the ancient Greeks established an Ecclesia – Assembly – which met on the Pnyx, a hill in central Athens, Greece. The Ecclesia met 40 times a year and was attended by male citizens who had completed their military training. Decisions were made by a show of hands, or voting with stones or pieces of pottery.

The Roman Republic, which was founded around 509 BCE, was ruled by 2 elected Consuls, who acted on the advice of the Senate – the council of elders. The Senate comprised 300 members from wealthy and noble families. Laws were approved by various assemblies, who represented the nobles and common people. These assemblies did not write new laws but met to vote on laws and elect officials.

Locations of the origins of the concepts of parliament

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

A simplified map of Europe and West Asia (modern-day Syria and Iraq). Highlighted on the map are Rome (509BCE), Athens (500BCE) and Mesopotamia (2500BCE).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Early assemblies in England

The British Parliament has its origins in 2 early Anglo-Saxon assemblies – the Witan and the moots.

The Witenagemot – Witan – dates back to the eighth century and advised the monarch on matters such as royal grants of land, taxation, defence and foreign policy. Witan comes from the Anglo-Saxon phrase Witana Gemot, which means 'meeting of the wise men'.

The Witan did not have a permanent membership but was made up of advisors and nobles who met when called by the monarch. Although the Witan had no power to make laws, the monarch was careful to consult the assembly because they relied on the support of the nobles to rule.

In 1066 William the Conqueror invaded Britain. William ruled with the help of a much smaller but permanent group of advisers known as the Curia Regis – King's Council. It consisted of noblemen and church leaders appointed by the King. They were not elected and so did not formally represent anyone.

Like the Witan, which it replaced, the Curia Regis only offered advice at the King's request and he did not have to act on this advice. The King sometimes consulted a larger group of nobles and churchmen known as the Magnum Concilium – Great Council. Over time, the Great Council evolved into the House of Lords.

The moots were local assemblies held in each county and shire to discuss local issues and hear legal cases. They were made up of local lords, bishops, the sheriff and 4 representatives from each village. The practice of local representatives making decisions for their community eventually led to the creation of the House of Commons.

A written agreement – the Magna Carta

Inspeximus issue of Magna Carta, 1297

Parliament House Art Collection, Department of Parliamentary Services

Inspeximus issue of Magna Carta, 1297

Parliament House Art Collection, Department of Parliamentary Services

Description

The Magna Carta was important in the development of democracy and has influenced many other documents including the Australian Constitution. This 1297 copy of the Magna Carta is displayed at Australian Parliament House. The 1297 Inspeximus issue of the Magna Carta is a rectangular document which is covered in small writing. The text is written in Latin on parchment, and the document features the royal seal of King Edward I.

Copyright information

Permission for publication must be sought from Parliament House Art Collection. Contact DPS Art Services, phone: 02 62775034 or 02 62775123

In the early 13th century King John of England waged a long and drawn-out war with France, which was largely funded by taxing the feudal barons. Under feudal law, the King granted the barons land – fiefdoms. In exchange he demanded money and troops. This meant the barons had to impose taxes on the people in their fiefdoms. The King's use of the justice system to suppress his opponents had also caused widespread discontent. In 1215 the barons rebelled, fed up with King John's demands and his failure to consult them.

In June 1215, one month after the rebellion started, King John was forced to agree to the Magna Carta – the 'Great Charter'. It limited the King's power by making him subject to the law, not above it. The Magna Carta also confirmed feudal customs and the operation of the justice system, and recognised that the barons had a right to be consulted and to advise the King in the Great Council.

While most of the Magna Carta described the division of power between the King and the barons, it also made reference to the rights of individuals. One of the most celebrated sections is credited with establishing the principle of a right to a fair trial. It states:

No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.

This declaration of individual rights has been seen as an important step towards the development of democracy, and has influenced documents such as the Australian Constitution and the American Bill of Rights.

Rebellion to representation

In 1236 an assembly between the English monarch and his advisors was described as a parliament for the first time.

Despite the reforms of the Magna Carta, King John's successor, King Henry III, continued to clash with the barons. Many of the barons were unhappy with Henry's rule, including his failed military campaigns in France and his choice of advisers and allies. Townspeople resented the King's tax demands and interference in their affairs.

In 1258 the barons forced the King to agree to rule with the advice of a 15-member council of barons and to consult with parliament more regularly. They wanted parliament to meet 3 times a year and to include 12 non-noble representatives chosen from the counties. However, King Henry did not honour the agreement and the opposing barons, led by Simon de Montfort, went to war against him.

De Montfort was a baron who believed the King's power should be limited, with more influence given to county knights and burgesses – representatives from the cities and towns. In 1264 he defeated the King and became, in practice, Britain's ruler.

The following year, de Montfort attempted to boost the support of the barons by calling knights from the countryside and burgesses from cities and towns to attend his own parliament. This was the first time commoners had been represented at such a meeting, although their attendance would not become permanent for another 63 years. The inclusion of commoners in de Montfort's parliament has meant it is seen as the forerunner of modern parliaments.

Soon after this parliament met, de Montfort was killed in battle by Henry III's son, Edward. Unlike his father, King Edward I met with parliament more regularly. Edward's parliament included 2 elected representatives from each county, city and town, making it more representative of the people. This provided a model for the future House of Commons.

The emergence of a parliamentary model

From 1327 the people's representatives sat in Parliament permanently and by 1332 were referred to as the House of Commons. The British Parliament now comprised 3 familiar elements: the monarch, the House of Commons and the House of Lords. However, it had no formal meeting schedule and continued to meet at the request of the monarch.

At this time, the House of Lords had far more influence on the monarch than the House of Commons and a greater say in the decisions of Parliament. However, in 1341 the House of Commons began meeting independently of the House of Lords and its power started to increase.

One of the main functions of the Commons was to petition the monarch and the House of Lords to resolve local and national issues by making new laws. These petitions often formed the basis of bills – proposed laws. It also became practice for the monarch to seek the approval of the Commons for new taxes because these taxes often had the greatest impact on the people represented by the Commons.

King Edward III's ongoing wars with France in the fourteenth century required him to call Parliament more frequently to raise money. The King's need for money gave the Commons leverage – bargaining power – to request concessions in return, including that the King and House of Lords act on their petitions.

By the mid-fifteenth century, rather than simply petitioning the House of Lords, the Commons had gained equal law-making powers. The Commons was also responsible for granting the monarch access to money raised by taxes. Today, its law-making powers are greater than those of the House of Lords.

Key reforms achieved by the House of Commons in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries

| 1362 | New law states Parliament must approve all taxes. |

| 1376 | Sir Peter de la Mare, a member of the House of Commons, is chosen by the Commons to act as its spokesperson before the King, making him the first unofficial Speaker. |

| 1377 | Thomas Hungerford becomes the first official Speaker of the House of Commons, responsible for running its meetings and representing its views. |

| 1407 | Proposals for taxes must come from the Commons, removing this power from the King. |

| 1414 | Parliament agrees that no bill can become law without the agreement of the House of Commons, nor can the King or the House of Lords change the wording of any bills submitted by the Commons without its approval. |

Parliamentary independence

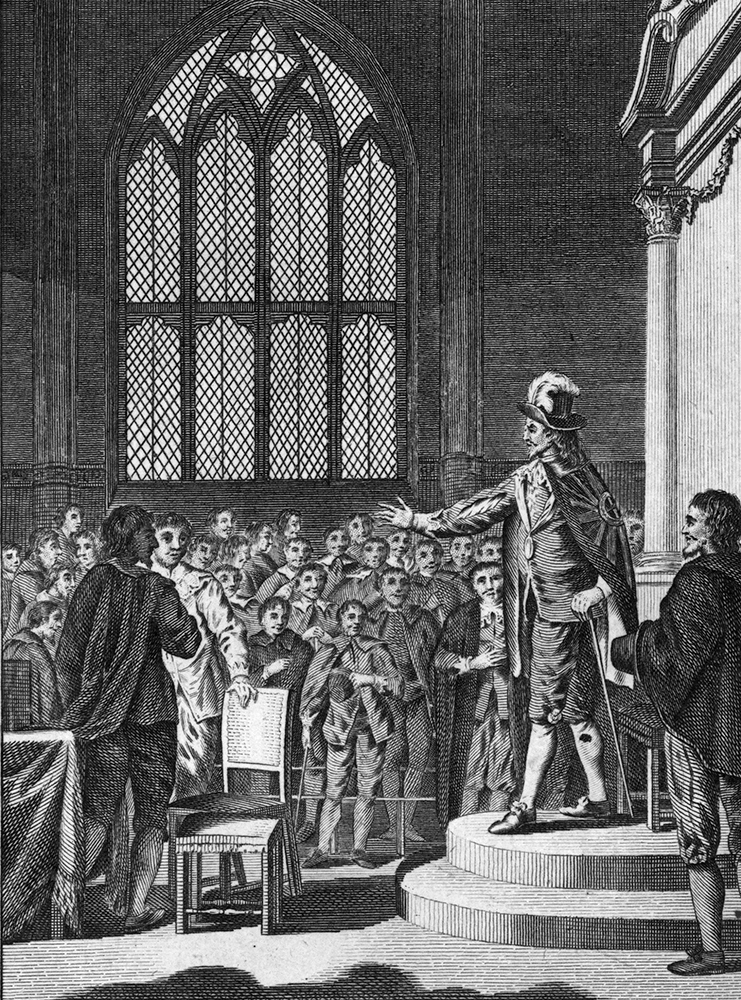

King Charles I of England entering the House of Commons

Description

King Charles I, recognisable by the large feather in his hat, decorated cloak and cane, is addressing the House of Commons. This illustration depicts the moment on 4 January 1642 when King Charles I entered the House of Commons to arrest 5 members of Parliament. He stands on the Speaker's platform and the clerks stand at their table in front of him. The members of the House of Commons look on. King Charles I went in the House of Commons to arrest members who were responsible for writing the Grand Remonstrance, which was a list of grievances against the king’s policies and actions.

The independence of the House of Commons from the monarch was further strengthened in January 1642 after King Charles I tried to arrest 5 members of parliament.

The relationship between King Charles I and Parliament had been steadily deteriorating. Parliament was critical of the King's rule, including his taxes, the wars he fought and his refusal to call Parliament to meet. Some also feared Charles wanted to destroy the Protestant religion in England.

John Pym and 4 other members of the Commons drafted the Grand Remonstrance, a list of Parliament's complaints. The Remonstrance was agreed to by the Commons in November 1641. It was the first time the Parliament had so openly challenged a monarch.

Charles considered this to be treasonous. Accompanied by soldiers, the King entered the Commons chamber to arrest Pym and his 4 supporters but they had gone into hiding. The Speaker of the House, William Lenthall, refused to reveal where the 5 members were, claiming 'I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here'. Rebuffed, Charles replied 'I see the birds have flown' and left the chamber. The autonomy of the House of Commons from the monarch had been demonstrated. This incident started a tradition that the monarch never enters the lower house of Parliament.

The conflict between the Commons and the King resulted in a civil war, the execution of Charles I in 1649 and Britain being declared a republic. The monarchy was restored in 1660 but the monarch and Parliament continued to clash. In 1689 King William and Queen Mary took the throne and agreed to the Declaration of Rights, which acknowledged Parliament's independence, including its right to free speech and to meet frequently.

Towards a modern parliament

The late-seventeenth century in Britain saw the rise of 2 political parties – the Whigs and the Tories. These first political parties were not as formal and organised as modern political parties.

The Whigs believed the British Parliament should have more power than the monarch. During the 19th century, Whigs were in favour of change and reform, and became the Liberal Party. Today, they have evolved into the Liberal Democrats.

The Tories were more conservative and opposed to change. They supported the power of the monarch and the Church of England, and were unwilling to give the British Parliament more power. Today, they have evolved into the Conservative Party.

Parliaments around the world

Many countries around the world were influenced by the British Westminster system of parliament. Some were originally British colonies that directly copied the Westminster system for their own parliaments. Others have adapted the model for their own country.

Canada

Canada gained independence in 1867, after a history of both French and British colonisation. The British monarch is still the Canadian head of state and is represented by a Governor-General. Canada has a bicameral parliament made up of a House of Commons to which members are elected and a Senate to which members are appointed by the Prime Minister.

France

In 1789 a National Assembly made up of members representing the French people was formed. In 1791 it was joined by a second chamber of assembly. The current French Parliament consists of the National Assembly and Senate.

India

Since 1952 India has had a President and a parliament with 2 chambers. India's houses of parliament are the Lok Sabha, to which members are directly elected, and the Rajya Sabha to which members are elected by the legislative assemblies of India's states and territories.

New Zealand

From 1854 until 1951 the New Zealand Parliament consisted of a Governor (or Governor-General), an elected House of Representatives and a Legislative Council appointed by the government. In 1951 the Legislative Council was abolished.

United States of America

Since 1789 the United States (US) has been governed by a President and Congress. In the US, the people vote for the members of Congress – the House of Representatives and the Senate – and elect a President through an indirect voting system.

The colonial parliaments of Australia

For at least 50,000 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on these lands and practiced traditional cultures and languages. From the late 1700s, British colonies were established.

By the late 1800s, each colony had its own written constitution, parliament and laws, although the British Parliament kept the power to make laws for the colonies and could over-rule laws passed by the colonial parliaments. People in each colony were granted the right to elect their own parliaments. However, voting was often restricted to men with a certain amount of wealth and land.

| State | Upper House established | Lower House established | First elections |

| NSW | 1823 Legislative Council |

1856 Legislative Assembly |

1843 (elections two-thirds of Legislative Council) |

| Vic | 1851 Legislative Council |

1856 Legislative Assembly |

1856 (elections for both Houses) |

| Tas | 1825 Legislative Council |

1856 House of Assembly |

1856 (elections for both Houses) |

| SA | 1836 Legislative Council |

1857 (elections for both Houses) |

1857 (elections for both Houses) |

| Qld | 1860 (abolished 1922) Legislative Council |

1860 Legislative Assembly |

1860 (elections for both Houses) |

| WA | 1832 Legislative Council |

1890 Legislative Assembly |

1870 (elections two-thirds of Legislative Council) |

When the territories were created they were governed by the Australian Government. The Northern Territory was granted self-government in 1978 and the ACT followed in 1988. The territory parliaments have only 1 chamber – a legislative assembly – which is elected by the people of that territory.

Federal Parliament in Australia

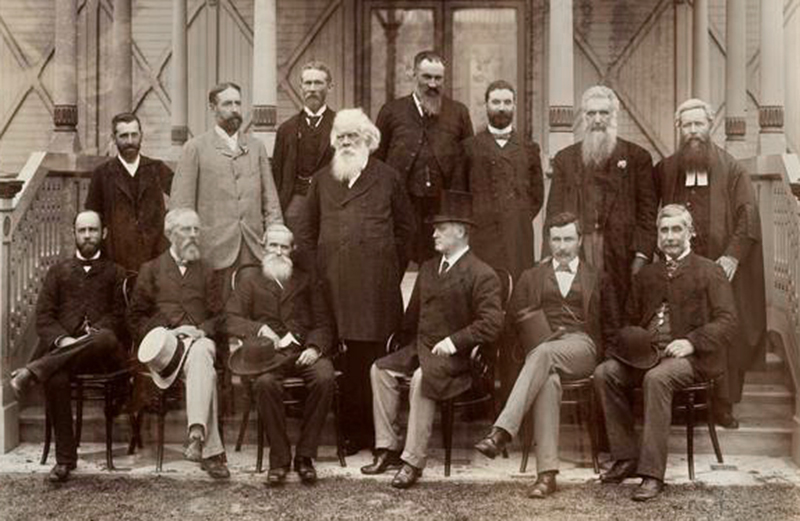

Members of the Australasian Federation Conference, 1890

National Library of Australia, AN14292110

Description

This sepia-toned photo was taken at the Australasian Federation Conference in Melbourne in 1890. These 14 men were delegates from the 6 Australian colonies and the colony of New Zealand. At the Conference, they discussed the idea that the colonies should unite. Notable advocate for Federation Henry Parkes is standing fourth from left, and Alfred Deakin (who would go on to become Prime Minister of Australia) is standing sixth from left.

Copyright information

You may save or print this image for research and study. If you wish to use it for any other purposes, you must declare your Intention to Publish.

In the 1890s a movement began to unite the colonies as one country with its own constitution. The Australian Constitution was drafted at a series of conventions – meetings – by representatives of the colonies and was approved by the Australian people who were eligible to vote in elections and referendums held in each colony. The British Parliament passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, which came into effect on 1 January 1901.

The Constitution united the 6 self-governing colonies into a new country – the Commonwealth of Australia. It established that in Australia:

- power would be shared between the federal – national – and state parliaments

- all members of parliament would be elected

- the Australian Parliament would be bicameral and represent the population overall (the House of Representatives) and the people in the states (the Senate).

Australia adopted the British tradition of responsible government, in which the Executive – the Prime Minister and ministers – are members of parliament. In order to remain in government, a party or coalition of parties must keep the support of the majority of members in the House of Representatives. This makes sure the Executive is accountable to the Parliament and does not abuse its power.

The first Parliament

The first federal elections for the new Australian Parliament were held on 29 and 30 March 1901. The Protectionist Party, who won 32 seats in the House of Representatives, formed a minority government with the support of other members in the House. Their leader, Edmund Barton, became the first Prime Minister.

Developments in the Parliament of Australia

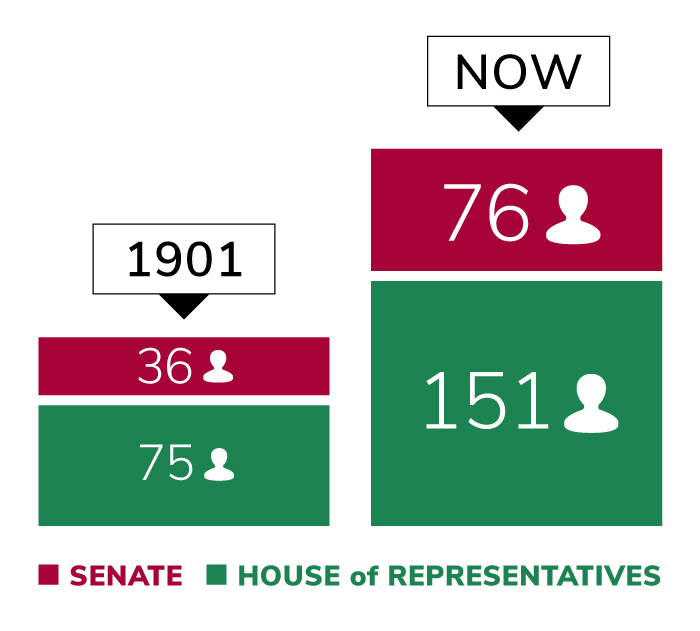

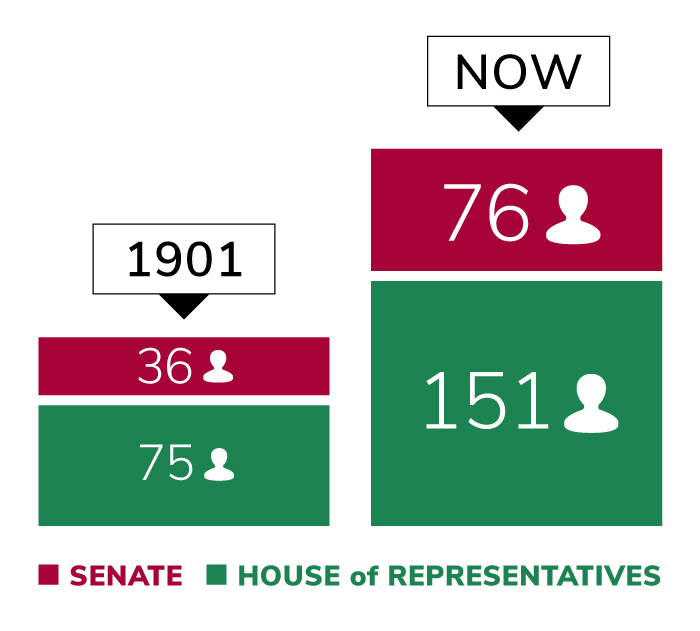

The number of senators and members of the House of Representatives in 1901 and now

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

The number of senators and members of the House of Representatives in 1901 and now

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The number of senators and members of the House of Representatives has changed since federation in 1901:

In 1901 there were:

- 36 senators

- 75 members of the House of Representatives.

Now there are:

- 76 senators

- 150 members of the House of Representatives.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

One of the most obvious changes in the Australian Parliament since federation has been the number of members of parliament. As Australia's population has increased so has the number of members of parliament. In 1901 the first Parliament had 75 members in the House of Representatives and 36 senators in the Senate. In 2025, there were 150 members and 76 senators.

Other changes have affected the voting system. In 1924 compulsory voting was introduced for federal elections. At the same time preferential voting began, in which voters were required to number their preferences for all candidates on the ballot paper. In 1948 proportional representation was introduced for the election of senators.

Parliament has become much busier as the House of Representatives and the Senate debate many more bills. Between 1901 and 1906 Parliament considered between 20 and 35 bills each year. Today around 200 bills are considered by Parliament each year.

In 1994 the House of Representatives established the Federation Chamber to give members more opportunity to debate non-controversial business. It is an extension of the House of Representatives and allows for 2 streams of business to be debated at the same time.