Rights in Australia

This paper investigates the framework of rights in Australia. It defines the different types of rights, including human rights, and looks at the many sources for our rights and how they are protected.

Rights are a key principle of Australia’s democratic system of government. Our rights come from a range of sources, including international law, common law (law made by courts) and statute (laws made by parliaments). How we define our rights in Australia has changed over time and may continue to change in the future.

What are rights?

A right is a moral or legal entitlement to have or be able to do something. Rights are created by laws.

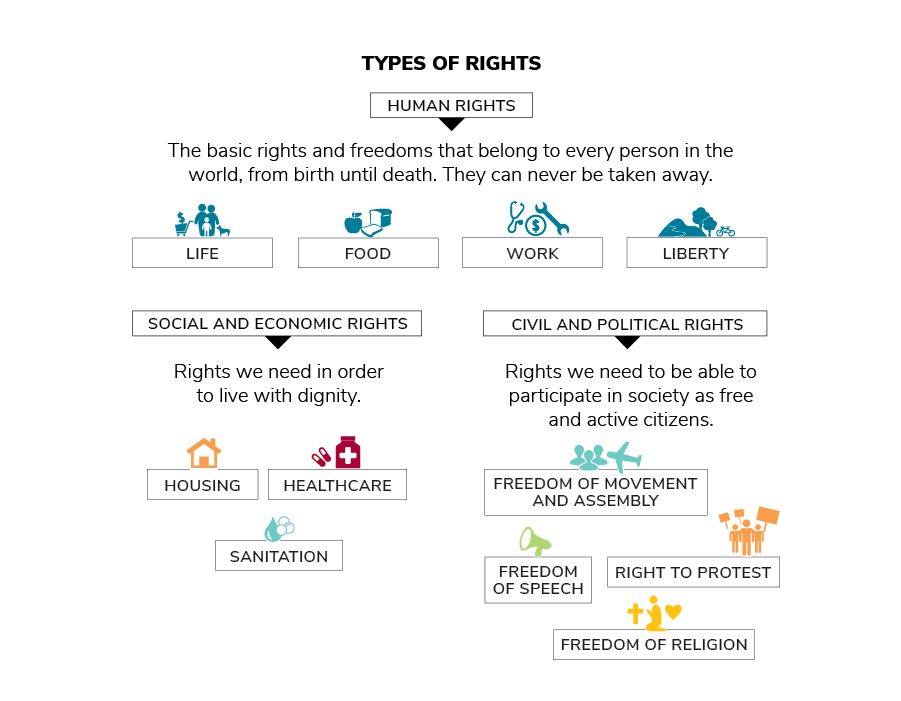

Rights can describe things that we should all be able to access, such as the right to housing, to healthcare, to sanitation, and to education. These rights are sometimes called social and economic rights because they describe what we need to have access to in order to live with dignity.

Rights can also describe actions that we should be free to do without interference by the government or other groups. This includes the right to practice a religion, to meet in groups, to express our opinions and to protest. These rights are sometimes called civil and political rights because they describe what we need to be able to do to participate in society as free and active citizens.

Human rights are rights that all people are entitled to, no matter who they are or where they live. They are protected by international law. They include social and economic rights, and civil and political rights.

Types of rights

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

Social and economic rights are rights we need in order to live with dignity:

- housing

- healthcare

- sanitation

- food

- education.

Civil and political rights are rights we need to be able to participate in society as free and active citizens:

- freedom of movement and assembly

- freedom of speech

- right to protest

- freedom of religion.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Sources of rights in Australia

Customary law

For over 60,000 years Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived in Australia. Many First Nations communities continue to practise their own customary laws. Customary laws are legal systems and practices uniquely belonging to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. They govern all aspects of life, including a person’s responsibilities towards others, to land and to natural resources.

The diversity of customary laws reflects the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples under customary laws are not uniform across the continent.

The Australian Constitution

The Australian Constitution is the source of some civil and political rights. The right to a trial by jury for federal offences and the right to practice a religion without interference from the Australian Government are 2 civil and political rights mentioned in the Constitution.

A key role of the High Court of Australia is to interpret the Constitution. By analysing and interpreting its text and structure, the High Court has found implied rights in the Constitution. For example, the High Court has found that because the Constitution establishes a representative democracy in Australia, individual citizens must have an implied right to freedom of political communication. This is because a representative democracy cannot function if people are not free to express their opinions on political matters.

Rights included in the Australian Constitution

|

The right to vote |

|

|

The acquisition of property by the Australian Government must be ‘on just terms’ |

|

|

Trial by jury for some offences |

|

|

The freedom to practice any religion |

|

|

State parliaments can not discriminate against non-residents of that state |

|

|

Implied rights |

Only courts have the power to find people guilty of an offence; the Australian Parliament can not pass a law that would impose a criminal conviction |

|

Freedom of political communication because the Constitution created a system of government based on representative democracy |

International law

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organisation that was formed in 1945, in the aftermath of the Second World War, to promote international peace and security. Since its formation, the UN has created a wide body of international human rights law, including over 80 human rights agreements.

Australia has signed many international human rights agreements. This includes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which is considered the world’s foundational human rights document. It consists of 30 articles that detail the basic rights of all people, creating a minimum standard for all nations to aspire to.

From 1945 to 1948, Australia – with many other countries – negotiated and drafted the UDHR. Dr H V Evatt, Minister for External Affairs and a former High Court judge, was president of the UN General Assembly when the UDHR was adopted in Paris on 10 December 1948.

Since the UDHR was adopted by the UN General Assembly, human rights law has expanded to include other international agreements. Many of these relate to the rights of specific groups in society, such as women, children, persons with disabilities and Indigenous people. Protecting minority groups vulnerable to discrimination is an important function of human rights in a democracy.

The 7-core international human rights treaties

Australia has agreed to all these treaties

It is important to note that international law, on its own, is not enforceable or binding in Australia. This is because Australia is protective of its sovereignty.

When the Australian Government commits to an international human rights treaty, it takes on an obligation to incorporate the treaty into Australian law. This does not happen automatically. A bill – a proposed law – that puts the international agreement into action needs to be passed by the Australian Parliament, or state or territory parliaments. If agreed to, the bill becomes Australian statute law.

Statute law

The Australian Parliament plays a central role in putting Australia’s human rights obligations into action. This is because all new domestic laws for Australia must be agreed to by the Senate and House of Representatives.

The Australian Parliament has passed laws that enact Australia’s human rights obligations. These laws make it illegal to discriminate against vulnerable groups in society. They include:

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984

- Racial Discrimination Act 1986

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992

- Age Discrimination Act 2004

The states and territories also have their own laws. If any part of one of these laws conflict with a federal law, that part of the state law will be overridden.

Common law

Common law – law made when judges make decisions in courts – is another source of rights in Australia. For example, in the case of Mabo and Others v Queensland (No 2) (1992), the High Court recognised that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have rights to their land – rights that existed before the arrival of the British and which continue to exist today. The Australian Parliament passed the Native Title Act 1993 after the Mabo decision to create a framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to seek legal recognition of their land rights.

Australian courts also follow customs, conventions and rules that uphold the rights of those who appear before them. This includes the right to a fair trial. For a trial in Australia to be fair, it should be held in public, the defendant should have access to a lawyer and judges should give reasons for their decisions. The right to a fair trial is recognised in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Australia has agreed to.

Australian courts sometimes look to Australia’s international treaty obligations when interpreting laws made by Parliament. When there is a gap in the law or uncertainty, they may look to human rights treaties and other international law for guidance. As a general rule, judges presume Parliament does not intend to limit the fundamental rights of Australians.

Australian common law was inherited from the British courts. Some rights come from common law made in British courts before Australia’s legal system became independent from Britain.

Protecting Human Rights in Australia

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

On 10 December 1986 – International Human Rights Day – the Australian Parliament passed an Act to establish the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC). The AHRC is an independent government organisation that plays a key role in protecting and promoting Human Rights in Australia. Australians can make a complaint to the Human Rights Commission if they have experienced discrimination in their public life on the basis of their race, gender, age, ability or sexual preference. After an investigation involving both parties, the AHRC will resolve the complaint through a free, informal and impartial process known as conciliation.

The AHRC can also investigate complaints about breaches of human rights against the Australian Government or one of its agencies. For such a complaint to be investigated, the government’s actions must appear to breach an international human rights agreement that Australia has agreed to. After conciliation, the President of the Human Rights Commission may write a report about the matter that recommends the Australian Government change its policies or practices. The Commission cannot make the Government act upon its recommendations.

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 established the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights which is responsible for scrutinising – closely examining – all bills introduced to the Australian Parliament to see if they are compatible with the 7 core human rights treaties Australia has agreed to. The Committee can also examine laws made by the Australian Parliament in the past for their compatibility with these human rights treaties. The Committee uses its findings to provide advice on the human rights compatibility of a bill to the Senate and House of Representatives. The Committee cannot force Parliament to follow its advice but its findings can be influential. Although the Committee’s main role is to scrutinise bills, it can also conduct inquiries into human rights issues in Australia when directed to by the Attorney-General.

An Australian Bill of Rights?

A Bill of Rights is a list of the most important rights belonging to a country’s citizens. It is usually passed as a law through parliament and belongs to the domestic law of the country. New Zealand and Britain both have a legislated Bill of Rights. In some countries, such as in the United States, India and East Timor, a Bill of Rights is part of the country’s constitution.

In Australia, the ACT, Queensland and Victoria have their own human rights laws. These apply in those states and territory only. At the national level, Australia does not have a Bill of Rights. This makes Australia the only democratic country in the world without a national bill or charter of rights.

If Australia were to have a Bill of Rights, it would list in one document some or all of the rights currently defined by international law, federal laws, the Constitution and common law. It could just include civil and economic rights, or it could also list social and economic rights.

Those in favour of a Bill of Rights for Australia claim it would make rights directly enforceable, and therefore strengthen our democracy. Others argue that our rights are adequately defined by other sources and that a Bill of Rights is not necessary.

If Australia did have a Bill of Rights, it would need to be agreed to by Parliament. Parliament would need to decide – as representatives of the people – which rights would and would not be included. Parliament could also add or remove rights by amending – changing – the bill in the future.