The Australian Constitution in focus

The Australian Constitution is the legal framework for how Australia is governed. This paper explores in detail the history of the Constitution, its key features and the High Court’s role in interpreting it.

What is a constitution?

Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, 1900: Original Public Record Copy (1900).

Parliament House Art Collection, Art Services Parliament House

Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, 1900: Original Public Record Copy (1900).

Parliament House Art Collection, Art Services Parliament House

Description

This image shows the front page of the original public record copy of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900.

Copyright information

Permission for publication must be sought from Parliament House Art Collection. Contact DPS Art Services, phone: 02 62775034 or 02 62775123

A constitution is a set of rules by which a country or state is run.

Some countries have unwritten constitutions which means there is no formal constitution written in one particular document. Their constitutional rules come from a number of sources. Britain sources its constitution from a number of important laws as well as principles decided in legal cases and conventions. New Zealand has a number of documents that comprise its constitution.

Other countries have formal written constitutions in which the structure of government is defined and the powers of the nation and the states are written in one single document. These systems may also include unwritten conventions – traditions – and constitutional law which can inform how the constitution is interpreted. Australia, India and the United States are examples of countries with a written constitution.

Some constitutions may be amended – changed – without any special process. The documents that make up the New Zealand Constitution may be changed simply by a majority vote of its Parliament. In other countries a special process must be followed before their constitution can be changed. Australia has a constitution which requires a referendum in order to change it.

The Australian Constitution

The Australian Constitution is the set of rules by which Australia is governed. Australians voted for the Constitution in a series of referendums. The Constitution establishes the composition of the Australian Parliament, describes how Parliament works and what powers it has. It also outlines how the federal and state Parliaments share power, and the roles of the executive government and the High Court of Australia . It took effect on 1 January 1901.

In addition to the national Constitution, each Australian state has its own constitution. The Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory have self-government Acts which were passed by the Australian Parliament.

Constitutional conventions

For at least 60,000 years Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on these lands and practiced traditional cultures and languages. From the late 1700s, British colonies were established. By the late 1800s, these colonies had their own parliaments but were still subject to the law-making power of the British Parliament.

During the 1890s colonial representatives came together at special meetings called ‘constitutional conventions’ to draft a constitution which would unite the colonies as one nation and provide for a new level of national government.

Each Australian colony sent delegates to the conventions. By 1898 the delegates had agreed on a draft constitution which they took back to their respective colonial parliaments to be approved.

Passing the Constitution

The final draft of the Constitution was approved by a vote of the people who were eligible to take part in referendums held in each colony between June 1899 and July 1900.

The Constitution had to be agreed to by the British Parliament before the colonies could unite as a nation. An Australian delegation travelled to London to present the Constitution to the British Parliament.

After negotiating some changes, the British Parliament passed the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill in July 1900.

Queen Victoria approved the bill on 9 July 1900 by signing the Royal Commission of Assent and the bill became the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. Section 9 of this Act contained the Constitution which stated that on and after 1 January 1901, the colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania would be united and known as the Commonwealth of Australia. Western Australia agreed to join the other colonies in a referendum held on 31 July 1900, 2 weeks after the Act was passed.

After Federation in 1901 Australia still had constitutional ties with Britain, particularly in the areas of foreign policy and defence. Since then the British and Australian parliaments have passed a number of laws which have given Australia greater constitutional independence. For example, in 1942 the Australian Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 which meant Australian laws could no longer be over-ruled by the British Parliament.

The Australia Act 1986 removed all remaining legal links between the Australian and British governments.

Key features of the Constitution

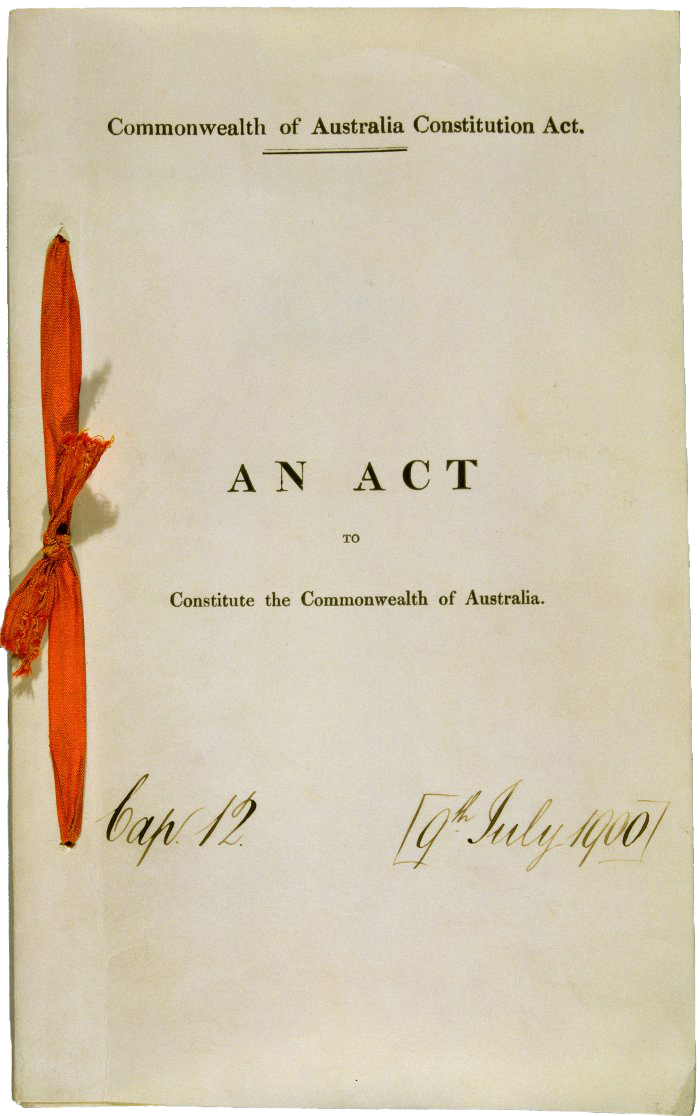

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 granted permission to the 6 Australian colonies, which were still subject to British law, to form their own national government in accordance with the Constitution. The Act consists of a preamble and 9 clauses, of which clause 9 is the original Australian Constitution. The Constitution consists of 8 chapters and 128 sections.

Chapter I describes the composition and powers of the Australian Parliament, which consists of the King and a bicameral legislature with:

- single-member representation for each electorate for the House of Representatives

- multi-member representation for each state for the Senate.

Chapter I contains sections 51 and 52, which list most of the areas in which the Australian Parliament can make laws. The Australian Parliament can make laws on a range of issues (such as immigration and pensions), but the Constitution allows other powers (such as providing roads and transport) to remain with the states.

Chapter II describes the power of the most formal elements of executive government, including the King, Governor-General and the Federal Executive Council.

Chapter III provides for the creation of federal courts, including the High Court of Australia, which is the final court of appeal. The High Court can interpret the law and settle disputes about the Constitution.

Chapter IV deals with financial and trade matters.

Chapters V and VI outline the relationship between the Australian Parliament, and the states and territories. Importantly, chapter 5 states that if the Australian Parliament and a state parliament both pass laws on the same subject and these laws conflict, then the national law overrides the state law. Section 122 in Chapter 6 gives the Australian Parliament the power to override a territory law at any time. It also allows the Australian Parliament to make laws for the representation of the territories.

Chapter VII describes where the capital of Australia should be and the power of the Governor-General to appoint deputies.

Chapter VIII describes how the wording of the Constitution can be changed by referendum.

The Australian Constitution does not include a bill of rights. However, some human rights are mentioned, including the right to compensation if the government acquires your property (section 51 (xxxi)), guaranteed trial by jury for federal offences (section 80) and freedom of religion (section 116).

The sections of the Australian Constitution

PARLIAMENTARY EDUCATION OFFICE (PEO.GOV.AU)

Description

Chapter 1 - The Parliament

Chapter 2 - The Executive Government

Chapter 3 - The Judicature

Chapter 4 - Finance and trade

Chapter 5 - The States

Chapter 6 - New states

Chapter 7 - Miscellaneous

Chapter 8 - Alteration of the Constitution

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

The Constitution and the High Court of Australia

People are allowed to test the meaning and application of the Australian Constitution. The High Court of Australia interprets the Constitution and settles disputes about its meaning. It has the power to consider national and state laws and determine if such laws are within the powers granted in the Constitution to the relevant level of government. The High Court can invalidate any law or parts of a law it finds to be unconstitutional.

Sometimes the High Court is asked to decide whether it is the Australian Government or a state government which has the authority and responsibility to deal with a matter. At other times, because the Constitution provides specific limits to what the Australian Government has the power to do, the High Court may be asked to decide whether a law made by the Australian Government is within that power.

How the Constitution can be changed

Double majority

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The Australian Constitution can only be changed with the support of the majority of Australian voters and the majority of voters in the majority of states (i.e. at least 4 states).

A referendum is passed when:

- a majority – more than half – of voters from all around Australia vote YES

- a majority – more than half – of voters in at least 4 states* vote YES.

*Votes from the ACT, NT and other territories are counted in the national majority only.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

The Australian Constitution can be changed by referendum according to the rules set out in section 128 of the Constitution. A proposed change must first be approved as a bill by the Australian Parliament before it is put to the Australian people to decide.

A referendum is a national ballot on a question to change the Constitution. In a referendum the Parliament asks each Australian on the electoral roll to vote. To be successful, the proposed change must be agreed:

- by the majority of people across the nation

- by the majority of people in a majority of states.

This is called a double majority.

Since the first referendum in 1906, Australia has held 20 referendums in which 45 separate questions to change the Australian Constitution have been put to the people. Only 8 changes have been agreed to.

Successful referendums have included:

- the 1946 referendum which allowed the Australian Government to provide social welfare payments

- the 1967 referendum (in which 90.77 per cent of people voted 'yes') which gave the Australian Parliament the power to make special laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- the 1977 referendum which gave the people of the territories the right to vote in referendums, changed the way casual Senate vacancies were filled and forced federal judges to retire at 70 years of age.

Unsuccessful referendums have included:

- the 1951 referendum which sought to give the Australian Parliament the power to make laws about communism and communists

- the 1999 referendum which asked whether Australia should become a republic.

How the Constitution is interpreted has also changed and evolved, even without changes being agreed to in referendums. These changes have not changed the words of the Constitution but have been brought about by High Court decisions. Two examples are:

- The Australian Government’s increased power to collect income tax has meant it has a much greater ability to raise money than the states. The Australian Government partly redistributes this money in the form of grants to the states. This has allowed the Australian Government to gain control of areas of responsibility the states previously controlled – for example, higher education.

- The Australian Government’s power over foreign affairs (section 51(xxix)) has meant laws to implement international treaties can be applied to the states in areas which were previously controlled by the states alone (such as environmental protection).

Case study 1 – Work Choices case

The 'Work Choices' laws, which came into effect in March 2006, made changes to the regulation of employment conditions and industrial relations. To make the changes, the laws used the 'corporations power' granted by section 51(xx) of the Constitution, rather than the conciliation and arbitration power in section 51(xxxv) that has historically been the foundation of Australia's industrial law.

The Australian Government’s use of the corporations power was challenged by the states and territories in the High Court, along with other aspects of the Work Choices reforms. However, the challenge was rejected by a majority of the Court and the laws were upheld.

Case study 2 – Tasmanian Dam case

Protesters at Franklin Dam site, 1982

National Archives of Australia: A6135, K16/2/83/4 Photo credit: Tasmanian Wilderness Society

Protesters at Franklin Dam site, 1982

National Archives of Australia: A6135, K16/2/83/4 Photo credit: Tasmanian Wilderness Society

Description

A group of protestors wearing warm clothes and wet weather clothing are kneeling or standing on a dirt road in south-western Tasmania. Their hiking packs are scattered around. An Australian flag and a 'No Dams' sign blow in the wind. A river and forest are in the background.

This photo was taken on 17 December 1982. The protest was against the Tasmanian Government's decision to build the Gordon-below-Franklin Dam (also known as the Franklin Dam).

Copyright information

Various copyright conditions apply to content in the National Archives collection, depending on the type of material and its age.

For permission to reproduce images and records from the collection, submit a copyright request.

Advice about copyright of material in the National Archives collection can be found in Fact Sheet 8 – Copyright.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Australian Government and the Tasmanian Government fought over whether a dam should be built on the Franklin River in Tasmania. After a long campaign, the area was placed on the World Heritage List in 1982.

The next year the High Court ruled the Australian Parliament’s external affairs powers in section 51(xxix) of the Constitution gave it the right to honour its international treaty obligations with regard to World Heritage locations.

This overruled Tasmania's constitutional land use rights and stopped the building of the dam.